By Milina Jovanovic

The Serbian American residents of Amador County have the longevity that is not present in other Bay Area communities. Just imagine…the great-grandfathers and great-grandmothers came [to Jackson] 110 years ago. The people who live here belong to the families of the original settlers in this area. They’ve been here almost as long as the French, and the Italian, and the Spanish, and the Irish…and together they’ve built this place now called Amador County. The people here have the longevity that you did not have in Moraga or Saratoga. In Moraga, a large portion of population came right after World War II and they have a different mindset. There were certainly Serbs in San Francisco in the 1850s, but proportionally they were not that significant. Here, in proportion to the total population, we have much more influence. The Serbian presence here is real. Others who live here but don’t have Yugoslav roots also know Serbian traditions. You know, there is this tradition here in Jackson that all merchants don’t take down their Christmas decorations until Serbian Christmas comes; this is an indication how influential our community is. Most definitely we’ve preserved our good reputation here. And the reason goes back to the fact that we were so influential. There was a solid basis here and people were not swayed by the propaganda. Because their neighbors were Serbian, their grandparents grew up with Serbians, they knew that this doesn’t compute—it cannot be the right thing. But when they live in big metropolitan areas with a lot of people who came from all over the world, there is not the same foundation to build upon, or to challenge the information that is being fed to them. They have been told an untruth about Serbian Americans and now they have to undo it. - Reverend Stephen Tumbas, St. Sava Church, Jackson, California, 2005

Jackson is the county seat of Amador County, California, situated in the Sierra Nevada foothills at the junction of highways 88 and 49, 50 miles southeast of Sacramento. Immigrants from the Yugoslav region originally settled in this Mother Lode region during the California Gold Rush and ever since, a prominent Serbian American community has resided there. This article will focus on Serbian American contributions to Amador County over the past century and a half.

.Because most of the material in the paper was based on personal interviews with members of the Serbian community in Jackson, some of the following story will be told by those interviewees. In the past 20 years people of Serbian background have been denigrated in the popular culture and scholarly works, largely influenced by the demonization of Serbs before, during, and after the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s. [See: Foerster, Lenora, ed. War, Lies and Videotape: How the Media Monopoly Stifles Truth. 2000. N. Y.: International Action Center. During the 1990s, in order to justify foreign policy goals and interventions, the U.S. and NATO used material generated by Ruder Finn Global Public Affairs public relations firm. Bosnian and Croatian governments hired the firm and relied heavily on its propaganda. Also see about negative media, public, and academic images of Serbs and Yugoslavs: Parenti, Michael. 2000. To Kill a Nation: The Attack on Yugoslavia. N. Y.: Verso, p.81-95; Grubacic, Andrej. 2010. Don't Mourn, Balkanize. Oakland: PM Press, pp. 26-28, 42 & 124-131; Todorova, Maria. 1997. Imagining the Balkans. N.Y: Oxford University Press, pp. 107-120]

In this article I will begin by discussing the methodology used in my research into the community. Next, I will highlight contributions made by the Serbian community in California between 1850 and 1900 and those of Serbian American women during the major part of the twentieth century. I will note contemporary contributions of Serbian Americans, discuss the image of the Serbian American community, and explore major issues facing Serbian Americans in Amador County today. Finally, I will introduce some questions for future research.

Methodology

Serbian Americans, in spite of having lived in Northern California for 150 years, constitute a community whose contributions to the development of the region are known to only a small number of researchers, scholars, and laypeople. The research I conducted in 2003-2007 focuses on the long history that Serbian Americans share with other residents of Amador County. [Eterovich, Adam. 2003. Gold Rush Pioneers from Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Boka Kotor. San Carlos, CA: Ragusan Press, pp. 26-29 & 63-76; A. Eterovich also emphasizes that the Yugoslav Americans have had a major role in the development of this region and California as a whole in the past 150 years.] My research included a combination of qualitative and quantitative methodological techniques and is an attempt to present a version of "people's history" rather than a removed historian's views. Only a few academic works focus on the history of Serbian Americans and their contributions using this approach. [The existing literature that focuses on the lives of Serbian and other Yugoslav Americans and documents their contributions is more ethnographic in nature than sociological or anthropological, with a few exceptions such as Karlo (1984); Mace (2004); De Grange (1998); and one immigrant account by Adamic (1934) that bring people's voices to life.] One of these sources is Jerome Kisslinger's The Serbian-Americans, published in 1990. He notes that Serbian immigrants were diverse in their social and political views and their understanding of what being Serbian American meant, but many threads kept them together. [Kisslinger, Jerome. 1990. The Serbian-Americans. NY & Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers, p. 17.] It is especially important that Kisslinger mentions not only the contributions of such prominent Serbian Americans as inventor Nikola Tesla, communication and technology researcher Mihajlo Pupin, actor John Malkovich, and Basketball Hall of Famer Pete Maravich, whose contributions are recognized by the entire American society, but also the role of miners and factory workers. Kisslinger adds that Serbian Americans are "woven into every fiber of the [American] social fabric." [Ibid, p. 17.]

While doing research, I was presented with invaluable material that included numerous previously untold stories of Serbian miners, educators, athletes, county employees, county supervisors, state senators, war veterans, judges, sheriffs, police officers, sales representatives, winery and restaurant owners, medical doctors, veterinarians, actors, artists, and community activists. The people I interviewed shared their deepest insights, family histories, and precious memories, as well as written documents and photographs. They expressed hope that their individual and collective stories would be heard. In addition to 16 in-depth interviews, I also conducted two types of surveys with Serbian Americans who live outside of Amador County, and with local residents who don't have Yugoslav roots. The following pages represent a summary of a longer manuscript entitled: All Roads Lead to Jackson: A Case Study of Serbian-American Contributions in Amador County, CA Since the Gold Rush. [A book to be published in 2013.] This article presents a selection of summarized stories highlighting the contributions of the Serbian American community from the late 1850s into the twenty-first century. [Methodological concerns and timeframes are discussed at length in the larger manuscript.] The exact words of my interviewees are

presented in the sidebar interviews.

The Gold Rush and the First Serbian Immigrants: 1850-1900

Larry Cenotto, long-time Amador County archivist, asserted that it was gold mining that attracted the earliest Serbian immigrants to California. [Cenotto, Larry (1931-2012) in Logan's Alley, Volume II, 1988: Cenotto Publications, p. 248 Even before the gold rush started, a small number of Yugoslav immigrants were present in California. There are records of Dalmatian explorers and other Croatian immigrants coming to the United States and Mexico, as early as 1600s, and definitely before 1850s. Because of the confusion in data collection, especially prior to 1900s, the country of origin was not recorded accurately: it was usually marked as Austria-Hungary (or either of these countries), Turkey (Ottoman Empire), Venice or Italy—the Yugoslav territories were dominated by these powers. Adam Eterovich documents that the first immigrants from Croatia, Herzegovina and Boka Kotor started coming to the U.S. territories in greater numbers approximately 200 years ago. They first immigrated to Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Texas. Also, see: Eterovich, Adam. 2003. Gold Rush Pioneers from Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and the Boka Kotor. San Carlos, CA: Ragusan Press, p. 2]

According to the County's records, the first Serbian immigrants came to this area around 1852. One of the families who came that early was the Froelich family. George and Rosa Froelich were recorded as farmers in the Patron's Directory in Township No. 1, immigrants who most likely came from Dalmatia or Herzegovina. [History of Amador County, CA with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of its Prominent Pioneers. 1881. Oakland, CA: Thompson & West]

The 1860 census recorded the following families already living in Amador County: the Aurvich, Babaga, Botiza, Cargich, Gospodnetich, Kosich, Madich, Radich, Svainac, and Velcich families. [Eterovich, Adam. 1978. Yugoslavs According to the 1860, 1870 & 1880 Amador Census of Population. Palo Alto: Ragusan Press.] As Gold Rush-era placer mining evolved into a large-scale mining industry and California's population grew, hundreds, later thousands, of immigrants from different lands that later formed Yugoslavia arrived as new inhabitants of the gold country. They came to the U.S. and to California in search of a better life—it was very difficult to make a living in the Balkan rural and mountainous areas. Most people who came from Yugoslav territories called themselves "Slavonians." [There are several theories that explain the use of the term "Slavonian." None of the explanations refer to Slavonia as a part of Croatia.] The meaning of the word "Slavonian" is closest to the term "Yugoslav" or "South Slav." At that time, most Serbian immigrants came from the territories of Montenegro, Herzegovina, and Dalmatia, rather than from Serbia. Local historians record that by the mid-1870s the population of the Yugoslav community in Amador County had increased from 200 to over 1,000 people. [Information posted on the St. Sava Serbian Orthodox Church's website in 2005.] The Serbian population in Jackson was so significant in the 1890s that it comprised nearly one-third of the town's total population. [There is no accurate data. The first census information available is from this time frame when Yugoslav immigrants, including Serbian, were often recorded as Austrian, Hungarian or Italian, depending on the area dominated by these powers.] The population of the City of Jackson today still doesn't exceed 7,000 people.

Serbian immigrants were initially monolingual and spoke Serbian or Serbo-Croatian, written in Cyrillic alphabet. During the existence of socialist Yugoslavia, Serbo-Croatian was the official language; most Yugoslavs speak Serbo-Croatian, excluding large numbers of Slovenians and Macedonians. All of these languages belong to the family of Slavic languages. With time, many Serbian immigrants acquired certain English skills and became more integrated into the larger society. When Serbian children started school their English language skills exceeded their parents' abilities and many of them became the bridge between their families and the larger society. Many of my interviewees shared with sadness that their teachers forced them to change their names: Slavko became Sam, Ivo became Evo, Branko became Brian, Ilija became Elia, etc. In addition, most institutions of the larger society forced them to add an "h" to their last names to make pronunciation easier for English-speakers. [For example, Kostić was spelled as Kostich, Dabović as Dabovich, etc.]

The first and second generations of American-born children had a much better chance of becoming familiar with all aspects of life in American society, including the phenomenon of upward mobility. For example, Dalmatian Andrew Pierovich became a state senator in 1933, a judge in 1941, and served in many other capacities. Similarly, John Begovich became a county supervisor and state senator during the 1960s and 1970s; George Milardovich was the chief of police in the 1970s; Mike Prizmich served as the county sheriff for two terms and just recently left to serve at the state level. At the very beginning of immigration from Yugoslavia, the generations of their parents worked mostly in the gold mining industry selling their labor, often risking their lives. From the 1860s to the early 1900s only a few Serbian American men worked any other jobs. In the "old country" only a few of them were miners. Most of them worked as farmers, fishermen, and construction workers before coming to the U.S. The early Serbian miners were uprooted from their homeland and they were often homesick, but they continued to work hard. Mining was arduous, filling their lungs with toxic dust, causing them much pain, and in many instances, ending their lives prematurely. One of the examples that show the effects this dangerous work had on the Serbian community is the August 1922 Argonaut Mine disaster. Of 47 miners who died in the disaster, 11 were miners of Serbian descent. Other victims were Croatian, Italian, Spanish or Mexican, Cornish, Irish and Polish Americans. The community was devastated and organized a communal burial at the St. Sava Church cemetery. Mike Backovich, Sr., who was a miner himself, and a few of my interviewees whose fathers worked in the gold mines, all remembered vaguely their childhood experiences, including the sorrow and anxiety present in the air during the time of the disaster. All of them knew some miners who lost their lives. In spite of hardships and great risks, miners and their families continued to rely on the communal spirit the local Serbian American community provided.

A center of Serbian community life, and one of the oldest buildings in Jackson, is the St. Sava Church. Built in 1894, it was the first Serbian Orthodox Church established on the North American continent. The entire Amador County recognizes the importance of St. Sava Church. One of the murals in Jackson's city hall depicts the original church building, and the church is included on the National Register of Historic Places. It is also one of the three symbols of the City of Jackson. [See the 3 symbols on the home page of the City of Jackson: St. Sava Church, Kennedy Mine Wheels and National Hotel: http://ci.jackson.ca.us/] This church has always meant much more than a place of religious worship to Serbian Americans—it once symbolized home in the new country; today it is a material reminder that a vibrant community existed such a long time ago. It allowed the Serbian community to have its own space where it renewed its optimism and conviction that with hard work the next generations could have a better future. The idea for St. Sava Church began when Serbian immigrants established the St. Sava Church Organization in 1886. This organization played a major role in the building of the church. In 1893 Father Sebastian Dabovich [His original Serbian name was Jovan] came to Jackson from San Francisco. Elia and Elena Dabovich, immigrants from the Boka Kotor and well-known merchants in San Francisco, were his parents. Father Dabovich was the very first American-born Serbian priest and the first head of the Serbian Orthodox mission on the North American continent. [Today, we have many Serbian Orthodox Churches around the country. This was the very first Serbian Orthodox Church established on the continent.]

In the 1897-98 Russian Orthodox Messenger [Russian Orthodox Messenger, Vol. II, 1897-1898, # 2, pp. 43-45] Father Dabovich wrote about the origins of the Serbian Orthodox Church in California explaining that before he started providing services in Jackson, Serbs were part of the Orthodox community at Fort Ross. Father Sebastian, one of the first U.S.-born male children of Serbian descent in the San Francisco Bay Area, crossed oceans many times during his lifetime. Like many priests, he denounced material wealth and personal possessions. There are records showing that Father Dabovich worked tirelessly to promote understanding across different religions and to explain Serbian Orthodoxy. He developed one of the first English translations of the Orthodox liturgy and published a newspaper entitled Herald of the Serbian Church in America. [Dobrijevic, Mirko. 1994. The First Serbian American Orthodox Apostle: Archimandrite Sebastian Dabovich. in: Celebrating a Century: St. Sava Church. Jackson, CA: church publication. More about Father Dabovich in: Palandech, John. 1942. The Life and Work of an American Missionary: The Very Reverend Sebastian Dabovich. Chicago: Palandech Publishing House. Eterovich, Adam. 1976. Father Sebastian Dabovich and the Origins of the Serbian Orthodox Church in America. Palo Alto: Ragusan Press.]

St. Sava Church, its architecture and Byzantine bright icons, had some influence on the architecture of the region. St. Basil of Ostrog, the Serbian church in nearby Angels Camp, was built in a similar style in 1910. These were small wooden structures, with carved iconostases (solid screens showing religious art and separating the nave from the sanctuary), originally equipped to accommodate 50-60 people, at most. Over time, their original structure was preserved. Today, Amador County's larger community has adopted St. Sava Church as one of its symbols and major points of interest for tourists and historians.

Some of the pioneers who had a pivotal role in establishing the Serbian community in Jackson as well as in building St. Sava Church were: Micho Curilich, Todor Curilich, Risto Curilich, Tripo Curilich, Trifko Curilich, Father Sebastian Dabovich, Milosh Dragolovich, Nikola Dragolovich, Scepan Dragomanovich, Simo Dragomanovich, Panto Kojovich, Savo Lakonich, Petar Obradovich, Savo Savich, Joko Skulich, Tripo Vasiljevich and Andrija Vukovich. In 1902, members of the St. Sava Church Organization and other South Slavs joined together to form the St. Sava Benevolent Society of Amador County. [Ifkovic, Edward. 1977. The Yugoslavs in America. Minneapolis, MN: Lerner Publications Company. Pp. 25-6]

The Yugoslav community is often credited for contributions to the development of California's agriculture. The community in Amador County is no exception. Based on the Report of the Agricultural Experiment Station of the University of California at Davis, 1892-1894, Dalmatian immigrants introduced the Dalmatian fig to Amador County in 1893. This fig is sometimes called White Adriatic Fig. The California Agricultural Experiment Station concluded that in Amador County this fig grows smaller than the same fig in other locations, but very sweet and rich. Nowadays, many Californians enjoy Dalmatian fig spread without thinking much about its origin and history.

The Amador County region is well known for its Shenandoah Valley vineyards. The Yugoslav community, and specifically Dalmatian immigrants, introduced a special variety of Zinfandel, the Dalmatian grape, Crljenek Kaštelanski. The wines made of this grape are known to be concentrated and full-bodied, often are described as intense. [http://threegracesvineyards.com/vineyards.html] Currently, Milan Matulich has a very successful winery in Plymouth called Dobra Zemlja. [The interview with Milan Matulich is included in the forthcoming book All Roads Lead to Jackson written by the author. Dobra Zemlja means fertile soil.] Yugoslav and Balkan cuisines were mostly preserved within the family, even though a few Serbian restaurants existed, such as Dan Vukajlovich's cafes and restaurants. They used to be popular gathering places of the larger community in Jackson in the 1970s and 1980s.

Serbian American Women's Contributions During the Twentieth Century

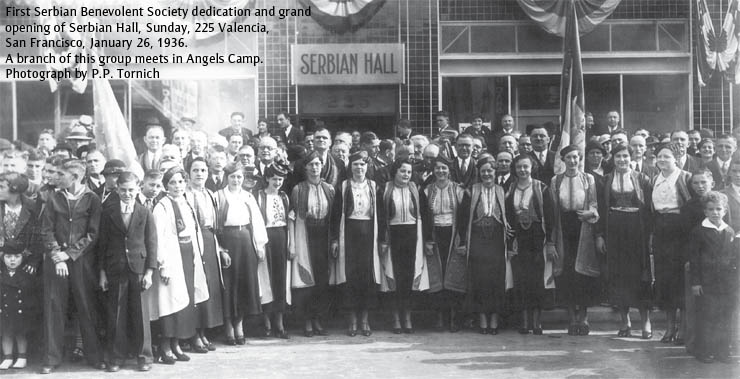

Serbian American women have made very significant contributions to the community of Jackson. Beginning in the 1850s, women operated boarding houses, produced food, and sustained their families and entire communities. In fact, women were also instrumental in cultural and linguistic preservation and social networking. They used their skills as homemakers and provided their homes, meals, and often laundry services to gold miners. Many maintained vegetable gardens and livestock. At the same time, Serbian women worked to form organizations. In the twentieth century, the most important contributions have been made through the women's organization—The Circle of Serbian Sisters (Kolo Srpskih Sestara, KSS)—initiated in Belgrade in 1903 and organized locally in 1936 in the home of Mare Curilich of Jackson. This organization has both religious and secular origins and purposes. It exists in Serbia and in the Serbian Diaspora and symbolizes the growing circle of women's connections. When it was established in Jackson, this was the first formalized Serbian woman's group in the area with a strong humanitarian purpose. The mission of the KSS here has been to connect Serbian American women with each other, with other religious and community organizations, and to provide support to the larger community. Some of their main activities have included the establishment of children's camps, publishing of the St. Sava Church & Mission annual publications and pamphlets, organizing retreats, fundraising [Jovanovic, Miroslava. 2010. "The Heroic Circle of Serbian Sisters." Serbian Studies, Vol. 24, No 1-2. Bloomington, IN: Slavica Publishers, p. 133], communication and various collaborations with the larger community, including with non-Serbian residents. Serbian American women aided WWII efforts by doing humanitarian work. In many instances, the Serbian community in their homeland looked at women as "emancipators" and "freedom fighters" since the Middle Ages as they participated in movements and armed struggles [40th Anniversary of Federation of Serbian Sisters' Circles. 1986. Grayslake, IL., p. 25]. The women in Amador County clearly liked that role. As an example, Ann Ingram, a Serbian American who lived her entire life in Jackson, was the first woman in Amador County to join the military and go to World War II. It seemed that the entire Amador County came out to send her to that mission with pride. [This information was shared in the interview with Ann Ingram conducted in 2005 and in the Amador Ledger Dispatch article published in 2004 for her 90th birthday.] In her self-identification, she never used the word feminist in my presence, but that's exactly how I saw her. Strong, creative, and active all the way into her mid-90s, Ann was an inspiration and role model for many.

In 1945, after World War II, The Circle held its first convention in the U.S. in Libertyville, IL. That was the occasion when the American Federation of Circles of Serbian Sisters was formed. Meanwhile, in Amador County of the early 1950s, a drive began under the direction of Reverend Milovan Shundich to build a church hall adjacent to the St. Sava Church property. At this time the Circle helped raise funds, organized dinners, and cultural events, and bought and donated equipment for the hall.

Women's activities of yesterday and today include food drives for all needy residents of Amador County, fashion shows, and collaborations with other communities. Women continue Serbian family and religious traditions, music and kolo dancing. They also help preserve multiple ties with the homeland. Whether doing humanitarian or educational work, connecting with friends and family who stayed in Yugoslavia, or bringing Serbian iconographers, artists and musicians, women had a key role in social networking and strengthening connections with their historical and cultural roots.

Women from Amador County also served in regional and national offices of KSS. The following residents of Jackson have served on the regional and national boards between 1960 and 1990: Anne Begovich Casagrande, Vera Davidovich, Sophia Ducich, Martha Kardum, Bessie Kosich, Ljuba Ljepava, Dorothy Milosovich, Mildred Popovich, Edith Perovich, Andja Polich, Dorothy Salata, and Olga Stanisich. At the St. Sava Mission one entire wall is covered with portraits of women who contributed in multiple ways to the Serbian community, St. Sava Mission, St. Sava Church, and Amador County at large. Portrayed are Anne Begovich Casagrande, Vera Davidovich, Sophia Ducich, Martha Kardum, Ljuba Ljepava, Sophia Marich, Draga Milkovich, Andja Polich, Stella Towers, and Amelia Zlokovich.

Andja Polich was instrumental in establishing a children's camp and the St. Sava Mission. Together with her husband, they donated funds and labor, helped establish a non-profit organization to oversee the Mission and tirelessly worked to leave a legacy to Serbian children. Every summer (and sometimes even during the winter), up to 400 children come to Jackson to continue learning about their Serbian roots, have fun, and find friends. Their families visit and many adult community members volunteer to work there as teachers, coaches, and kitchen workers. The Mission also created a fund and annually awards college scholarships to high school graduates in the U.S., Canada, and Serbia. This summer St. Sava Mission celebrated 50 years.

Contemporary Contributions of Serbian Americans and Their Image

Today, Serbian roots have taken hold in Amador County's soil, its symbols, and its culture. Important buildings, bridges, highways, public spaces, businesses, stores, tourist attractions, and even nationally protected places, have something Serbian in their name, image, or historical development. Serbian Americans have also preserved their positive image and good reputation. Furthermore, many residents have had a chance to learn the complex history and strong ties their Serbian American neighbors have to both the United States and Yugoslavia. This includes the multiplicity of reasons for Serbian immigration to the United States, and Serbian American contributions to the betterment of the larger society. Throughout the last 150 years locals have had opportunities to cross paths and share lives with many Serbian Americans as neighbors, colleagues, schoolmates, students, customers, and community activists. Each year on January 7th, major businesses and institutions close their doors and join in the celebration of Serbian Christmas. Many tourists participate in gold mining history tours and learn about the eleven Serbian and four Croatian Americans who died in one day, along with 32 others, in the 1922 Argonaut Gold Mine Disaster. [Mace, O. Henry, 2004. 47 Down: The 1922 Argonaut Gold Mine Disaster. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.]

Serbian Americans have influenced cultural and artistic trends by sharing Serbian traditions and celebrations with the larger community. This has included putting together theater plays based on the works of Serbian authors, performing annual recitals, and bringing their multiple talents to the Volcano Amphitheatre. The 2006 survey of Amador County residents who didn't have any significant ties to the Serbian community, or Yugoslav roots, confirmed that Serbian Americans had preserved their positive reputation in this region. The same view was expressed by the people I interviewed.

The number of Serbian Americans who currently live in the region is small, but the Serbian American community has stayed strong and vital. Many Serbian Americans who live elsewhere regularly come to Jackson. During the summer events, the community grows in size as many visitors attend the 4th of July celebrations, retreats, children's camps or three-day long gatherings of the Western (region) Orthodox Dioceses. These events also attract the larger community and visitors from Oregon, Arizona, Montana, and other states.

Some of the most representative contemporary stories include those of former sheriff Mike Prizmich, Danica Paul, Marie Kostich and Milo Radulovich. Sheriff Prizmich worked with the community to establish first shelter for victims of domestic violence and to improve the lives of young inmates who could see their children and play with them thanks to the program instituted by Prizmich. George Milardovich was the chief of police in the 1970s and had a pivotal role in controlling gambling and prostitution in Jackson.

Danica Paul seems to run almost everything in the Serbian community and organizes food drives for all needy people in Jackson. Marie Kostich, a very humble and quiet woman, will be remembered by the Amador County residents for her grace and for her traditional Serbian dishes that were adopted by the local Irish community as well.

Milo Radulovich had the first meteorological station in Jackson at the end of the 1950s and beginning of the 1960s. When Milo Radulovich passed away on November 19, 2007 even the dominant media finally acknowledged his pivotal role in American history and in defeating McCarthyism. Some called him a hero, some saw him as an important social justice activist who remained active for decades. Toward the end of his life he received special awards from the Michigan State Senate, Macomb County Bar Association (MCBA ' s first ever Medal of Achievement and Courage) and other institutions. His court case is considered a legal milestone when it comes to defending our civil liberties, and the Michigan State University Law School displays a plaque explaining the importance of that legal milestone (see Michigan Legal Milestone, above). George Clooney's film "Good Night and Good Luck" captured only some highlights from the most popular documentary program in CBS's history, "See It Now", in which Edward R. Murrow focused on Milo's situation in 1953.

The two current priests, the Rev. Miladin Garic and the Rev. Steve Tumbas, serve as community ambassadors of the local Serbian community. The Jackson community has preserved many ties with the homeland. During the Balkan Wars (1912, 1913), World War I, and World War II some of the men went back home to Serbia to join the military and found other ways to support families and friends who struggled with their oppressors and fought in the two world wars. During the most recent wars of the 1990s, some community members were able to travel to the war zone and then provide eyewitness accounts upon their return. The community also collected funds to send to orphanages, children's and maternity hospitals bombed by the U.S. & NATO in 1999, and joined various humanitarian efforts throughout the 1990s. During peaceful times, Serbian Americans host visitors from all parts of the former Yugoslavia, maintain open channels of communication, and promote educational exchange.

The Future of the Serbian American Community

The Serbian American community is also looking toward the future. Local community members are still dreaming, refining, and advancing their project of a unique Serbian Village that will include a retirement home, children's school and summer camp, recreational center, services for cultural and linguistic proficiency, and the St. Sava Church as a religious and cultural center. This center could be seen as California's "Little Serbia." Other larger immigrant groups have built and preserved such places throughout the United States. Larger Serbian communities in other parts of the United States such as the one in Chicago, IL, have many of the cultural elements needed for such a project, but even they have not yet fully developed a "Little Serbia." In Jackson, this project is still developing with the senior center and other components yet to be built. However, driving on Main Street from the St. Sava Church, passing by the John Petkovich Park, and continuing on Broadway towards the St. Sava Mission Center, it's a straight line leading to the "Serbian Village".

The present generations of Serbian Americans are facing great challenges. In today's globalized world it is not easy to preserve individual and group identities, cultural and linguistic traditions. The community in Amador County is currently small, with young people leaving the area in search of educational and employment opportunities. Many community members who were considered "living encyclopedias" because of their extensive knowledge of local history have passed away in recent decades. They belonged to generations that relied heavily on oral tradition. At the same time, the new generations are entrusted to preserve the legacy of several generations, the work that their great-grandparents started. How much will they be able to continue the legacy and move forward in Jackson as a symbolic home to Serbian Americans living on the West Coast and beyond? This will depend on many social factors shaping the present and future for all young people in today's world, Serbian Americans included. The Serbian Village is envisioned to connect the children with seniors who will have their retirement homes next door. Whether symbolically, or in reality, they would be able to meet and converse, bridge generational gaps, and continue to pass their stories on to new generations, generations that might become even more deeply rooted in the California soil.

Magazine CALIFORNIAN, Volume 34, January 2013

(published with author's permission)

Californian is published by the California History Center & Foundation

Sociologist Milina Jovanovic’s study of the Serbian/South Slav community in the Mother Lode city of Jackson, California, presented here in summary, featuring excerpts from three oral histories, addresses many issues of importance to all immigrant groups in America: obligations and connections to family, to fellow immigrants, to neighbor, and to country, both old and new; assumptions, prejudice, and stereotyping based on nationality, ethnicity, economic class, gender, and religious belief; relationships between occupation and individual/family well-being; organizations established for the permanence of the community; traditions chosen for preservation or discard in the new environment; political identity as equal members of a democracy; and courage and opportunity to become contributors to the development of their chosen homeland.

Jackson’s Serbian community put down new roots in that place because of factors common in the history of immigration to the U.S.— some negative, many positive. Jovanovic’s future publication of a monograph on this timely subject, as “people’s history”, promises to continue and enlarge discussion of these universal issues as it also focuses on the particular circumstances of this vibrant California community.