Since its inception, Christian iconography has always been closely connected to the cultures in which it developed. In fact, the basis of how we understand church art today is grounded in the secular artistic traditions of the Graeco-Roman world. Christian artists have been using pagan iconography and visual rhetoric ever since Christian art began to emerge.1) They borrowed heavily from both the pictorial and verbal elements that they found useful for the spreading the gospel message. For example, Christain artists adapted the figure of a sovereign God (characterized by a long hair and beard) such as Jupiter, as a representation of Christ because it expressed an idea of eternity to that culture.2) Similarly, the pagan image of the shepherd—a symbol of philanthropy in pagan Roman art—became the representation of Jesus Christ.3) This was probably due to its striking similarity to "the Good Shepherd" passage from John 10:11-16. The reasoning behind this process is that these familiar, if pagan, images were a better tool for preaching the gospel than creating a wholly new and unfamiliar set of images of a "purely" Christian origin. This enabled Christians to give new meaning to already familiar images and to thereby further an on-going cultural conversation. We would do well to learn from their example and truly engage our own culture.

This means that the Church must continue preaching its gospel, but do so in the artistic language of its culture. In order to do this and remain distinctivey Christian, Church art must also honor the traditional elements of its own iconography. These elements have been transmitted through a stable process of recension. Nevertheless, even if it is recensional, iconography is never sterile, closed off, or fixed, but always incorporates new elements in addition to the ones it has inherited from the tradition. As Lester L. Bundy notes: "It has always been characteristic of Orthodox iconography that the desire to maintain an historically dictated consistency in style, form, content, etc. exists in tension with the natural inclination for individual style and techniques."4) Iconography grows through a dialogue between the old and the new in the form of a commentary or what art historians call "text-and-gloss." Personal taste plays a large role in this dialogue: every generation adds a new layer of meaning, a new style in painting, and a new kind of figure to those already venerated in the tradition. New schools of iconography, show-casing their own regional traditions, have emerged as examples of this phenomenon.5) Thus, to continue the fucund tradtion of the Church we must create an original North American iconography that refelects the culture of North America and communicates the gospel to it. After all, iconography is supposed to be an expression of an authentic faith and not simply a copy of someone else's religious experience.6)

.This, however, is no easy task. Given the vast geographical size of the North America and its diverse demography, one can hardly speak of a single, unified North American culture. Clearly, even for the relatively small group of North Americans who identify as Orthodox Christians such a totalizing view would be absurdly simplistic and fail to reflect the real complexity of our situation. Rather, the Orthodox cultural situation in North America can be more accurately described as many different national and regional cultures co-existing through a cross-cultural identity.

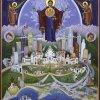

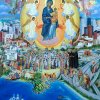

Like Orthodox Christians everywhere else in the world, the Orthodox of North America all share one crucially important feature in common: the same faith. This should be reflected in its iconography, just as it was in the historical Church. An icon that satisfies this requirement and can serve a possible model for North American iconography is the icon of Our Lady Theotokos Queen of Los Angeles (Example 1).7) The life of the Orthodox Church on the West Coast of the United States is characterized by a high level of Pan-Orthodox unity, and this icon was commissioned as an iconographic representation of this trend.8)

We have already seen that Orthodox iconography develops through a dialogue of recensional or inherited iconographical elements and those derived from local culture. Art historians call the inhertied elements "texts" and the new or local elements that interact with them "glosses." The icon of Our Lady Theotokos Queen of Los Angeles is a perfect example of this kind of dialogue: the figure of Theotokos with Christ is inherited (the "text") and the city she protects (the "gloss") is a realistic representation of a modern city of Los Angeles. As such, this icon is a synthesis of Byzantine and modern styles of painting.9)

The focal point of the icon is the figure of the Theotkos because she is positioned on the crossing point of the vertical and horizontal axes. The icon depicts the the Theotokos as a queen by presenting seated on a throne and motionless, facing the viewer. Eight figures flank her: four on her left and and four on her right. These figures can be identified as angels since they have wings as their attributes. One group of four angles form a procession and hold candles in their hands in order to show that they offer service to the Theotokos. The other group of four angels hold aloft a heavenly throne upon which the Mother of God sits. Therefore, the icon portrays the Theotokos as the Heavenly Queen and the Queen of the Angels. The icon is a reference to the original name of the City of Los Angeles—El Pueblo de la Reina de Los Angeles or The Town of the Queen of the Angels—given to it in 1871.10) The name shows that the city was placed under the protection of the Mother of God upon its construction and the icon embraces and develops this idea. As such, the icon both incorporates and interprets local culture and history.

A scroll with Psalm 133, 1: "Behold, how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity!" holds a central position in the lower half of the icon, where many figures engage in different activi-ties.11) Because the scroll is placed on the vertical axis (like the Theotokos in the upper half of the icon), it stands as an invitation to the figures in this lower, more worldly half to imitate the order an unity displayed in the upper half of the icon, where the Theotokos is seated on her heavenly throne among the angels.12) Two figures, whose mitres show them to be Orthodox bishops, hold up the scroll. Beside these two bishops, three other bishops, priests and faithful people surround the scroll.13) Mitres, Gospel books and censers, and civil clothing make these figures easy to identify. Together all these figures function as the scroll s flankers, just as the angels flank the Theotokos in the upper half. The hands of the bishops point to the scroll and the priests offer it incense; these actions emphasize the scrolls centrality in the icon. Further, the faces of the bishops are not generic; in fact, one can clearly recognize them as bishops of the different Orthodox jurisdictions in the city of Los Angeles.14) In order to draw the viewer's attention to the scroll, the icon contrasts the hands of the bishops with their gaze; while the bishops' hands point to the scroll, their gaze is directed at the viewer and serves as an invitation to understand the scroll's message. The gaze of the faithful, however, is directed to the members of the clergy, identifying them as their leaders. In addition to this, one can notice the presence of a number of real-life representations of local Orthodox churches, whose architectural style indicates that they belong to different jurisdictions. All of these things together show the ecumenical unity of the Orthodox people in the city of Los Angeles.

The lower half of the icon is filled with images of local culture and geography that gloss the inhertied elements, such as the Theotokos, in the upper half. Examples of this are: the cluster of skyscrapers placed right under the horizontal axis, the grape vine and the Ferris wheel on the left side toward the bottom, the farmers portrayed in the middle of the lower half, a group of musicians, and a strangely disembodied hand holding a basketball inscribed with the letters "NBA". All of these images also have a symbolic value and represent the different activities that the inhabitants of Los Angeles typically engage in, ranging from business, to agriculture, to entertainment. This means that the Mother of God helps the inhabitants of her city not only in their special hour of need, but also bestows her blessings on them in their normal, day-to-day lives. The central theme of the icon is unity of all Orthodox Christians of Los Angeles under the protection of the Queen of Angels.

In conclusion, one can say that only if we allow the traditional process of "text-and-gloss" to operate, then we will end up with an iconological meaning relevant to our time. This process necessitates introduction of new artistic elements, intellegible to the contemporary culture, in addition to the inherited ones. These new elements help transmit the message of the "text" by expressing it in a language contemporaneous with the culture. In this way, every generation of Christians becomes outfitted with iconological tools necessary for successful engagement of the culture that sorrounds it.

---

1) Andre Grabar, Christian Iconography: A Study of its Origins (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, —), xlvi

2) Ibid., 34.

3) Grabar, Christian Iconography, 11.

4) Lester L. Bundy, Modern Orthodox Iconography: A Neo-Byzantine Movement (xerox of an article, no reference to date or journal, SVS Library call number: VF 000725 ), 3.

5) Ibid., 3.

6) Davor Dzalto, New Faces of Icons (Belgrade: The Institute for Study of Culture and Christianity, Chicago: Holy Resurrection Serbian Orthodox Cathedral, 2012), 32.

7) There are two versions of this icon. Both icons were commissioned by Bishop Maxim of the Serbian Orthodox Diocese of the Western America. The one we will analyze was commissioned in 2008. The iconographer, nun Magdalene of the Kosovo Gracanica Monastery, worked on the icon for two years, and finished it in December 2010. The icon was brought over to the United States in December 2011. It is currently held in the Serbian Western American Cathedral in Los Angeles. Painting of another icon of this type is currently underway and is being done by Stamatis Skliris.

8) Bishop Maxim of the Western Diocese of the SOC, e-mail message to author, April 8, 2013.

9) Bishop Maxim of the Western Diocese of the SOC, e-mail message to author, April 8, 2013.

10) Bishop Maxim of the Western Diocese of the SOC, e-mail message to author, April 8, 2013.

11) The original inscription is in Serbian which presents us with a question of whether the icon was painted with a broader North American context in view, or it was intended only for a specific group of people with the purpose of furthering a pan-Orthodox understanding of the Church among them.

12) This idea was suggested to the author by John Boyd, ThM candidate at St. Vladimir's Seminary.

13) It is important to notice that on the other version of the icon, painted at the Ormilia Monastery (Halkidiki, Greece) by nun Hiliodora, all North American races are represented among the faithful, which really emphasizes the concern for culture and context in iconography.

14) These bishops are Metropolitan Gerasim of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, Archbishop Joseph of the Self-Ruled Orthodox Christian Antiochian Archdiocese of North America, Archbishop Kyrill of the ROCOR, Archbishop Benjamin of the OCA and Bishop Maxim of the SOC.

Vjekoslav Jovanovic